1) It could enhance your emotional intelligence

A study by David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano at New York’s ‘New School for Social Research’ suggests that reading literary fiction could make you more empathetic, if only temporarily. As the New Scientist reports:

They randomly assigned volunteers to one of three groups – literary fiction readers, popular fiction readers and a non-reading group. The first read extracts from texts shortlisted for the US National Book Award, while the second read extracts from Amazon.com bestsellers – popular fiction books with characters that are likely to be two-dimensional and straightforward to understand.

All three groups were then asked to identify the emotions behind facial expressions – a standard test of empathy. Those who had read the literary fiction showed a heightened ability to empathise compared with the other groups. The result was the same when they ran different tests with different volunteers (Science, doi.org/n5p).

The results were shortlived but there’s some scope to believe that prolonged reading could lead to longer term effects, and no doubt further research will expand on the (several) studies already completed.

Here’s what NPR had to say:

2) It fires up the imagination

It’s true that literary fiction can be a little more tell than show sometimes, but this doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Instead, it allows you to let your imagination run free, creating a world for you to inhabit for the length of the novel. In Elisabeth Camp’s essay ‘Two Varieties of Literary Imagination‘ (Midwest Studies in Philosophy XXXIII, 2009), Camp writes:

The simplest way in which fictions can alter our understanding of the real world arises as a direct result of the pretense itself: I might, for instance, gain a more intimate appreciation for the anguish of orphanhood, or for the attractions of gambling or being a bully, by empathizing with characters who undergo those emotions (cf. Currie 1995, 1997; Kieran 2003; Novitz 1987).

In this way, rather than following the characters, as is often the case when reading genre fiction, we are encouraged to step into the shoes of literary fiction characters. If portrayed correctly, we not only empathise with them, but also can imagine ourselves in their circumstances.

3) It’s a learning experience

Although not confined to literary fiction, authors who write literary works know there will be less scope for dramatic and/or potentially implausible or hyperbolic events to be used to enhanced the storyline. Instead, experiences and background become vital in building complex characters. Many authors draw on their own personal experiences when writing, and such works enhance our knowledge. They can force us to think hard about ethical dilemmas, see another side of the story regarding a controversial issue and so on.

Mitchell Green, of the University of Virginia, covers this brilliantly in his paper ‘How and What Can We Learn From Fiction?‘

[Sebold] draws on [her personal] experience in her account of Susie Salmon, the fictional teenager who is raped and murdered in The Lovely Bones. Her ability to do this adds to the power of the story, precisely by showing some dimension or dimensions of how that must have felt to the victim. By showing us how that experience felt, Sebold provides us with the tools for a disciplined use of our imagination: She guides us toward a proper understanding of what, or some portion of what, Susie Salmon must have felt while being raped and before her murder.

Some authors attempt to enable de se imaginings for what might seem impenetrable cases. In The Curious [Incident] of the Dog in the Nighttime, the author Mark Haddon tells a story from the point of view of an autistic boy, Christopher Boone. In some cases, you can imagine Christopher doing something but may find it hard to imagine yourself in his shoes: For instance, when upset he will calm himself with a repetitive activity, whereas I have no idea what it would be like to scrape a coin against a radiator for over three hours in order to calm myself down. In such a case we may engage in a de dicto, and perhaps also a de re supposition, but not a de se supposition. In other cases we do get some glimpse of what it would be like to walk in the boy’s shoes.

4) It’s often timeless

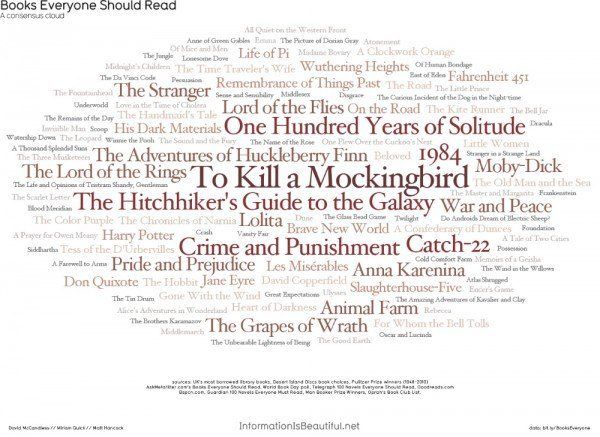

How exciting it is to think that the books we read now will still line our grandchildrens’ shelves? Or our great great grandchildrens’? On my shelf at home I have books that have been, and will be, enjoyed by generations. From, Shakespeare’s Othello (c. 1603), to Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847), to George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), literary fiction often covers issues that affect generations over and over. Whilst genre fiction can sometimes be constrained by changing political, technological and cultural landscapes, literary fiction persists. The emotions and the characters endure.

5) It offers great scope for discussion

Literary fiction is provocative and evocative. As such, it encourages discussion and debate. Take a look on Goodreads at the ‘Best Books of the Decade: 2000s‘ list. Many of the books on there are consistently highly rated but there are also plenty of readers who couldn’t find anything to like about the very same titles. I loved Norwegian Wood, for example, but my mother was less enamoured. I have tried – in vain – to read The Satanic Verses; despite my difficulties with it I know many others found it an incredibly compelling read.

Moreover, this discussion – while perfect for book clubs, reading groups and school classes – teaches us more than how to dissect fiction. A story in the Harvard Gazette, Truth in Fiction, explains:

“Students in my class react to characters in the book as if they’re real people. There’s a much deeper engagement in the actual material. It’s not about whether the debits and credits add up. They’re making comments about who they are and what they care about, and how they feel about the world that differs from their fellow students. It also reflects the student’s own character and judgment.”

Reading literature, and discussing complex issues with others, “teaches that people who are intelligent can see things differently,” says [Joseph L. Badaracco, the John Shad Professor of Business Ethics at Harvard Business School], “and this happens in organizations, too; you need to be open and listen to these differences.” Leaders have to recognize their biases and blind spots.

6) The language is often beautiful

Don’t shoot the messenger here; genre fiction can have beautiful language too. However, the constraints of ‘show don’t tell’ and the almost ‘Hollywood blockbuster’ style requirement that some genres seem to have, can make it difficult to expend extra words on beautiful fluidity for beauty’s own sake.

I’m not alone in loving this aesthetic approach to language. Sue Halpern, editor of NYRB Lit – the New York Review of Books ebook series – shared her thoughts earlier this year (The Guardian: Literary fiction – in a class of its own):

Halpern’s definition of literary fiction seems like a winning one too: it stands out for its “allegiance to language”. And so NYRB Lit’s growing catalogue makes a virtue of language and literacy; recent titles include translations of Kiran Nagarkar’s Ravan and Eddie, a Marathi tale of two boys growing up in Bombay; Markus Werner’s On the Edge, which sold 40,000 copies in Germany alone; and Yoram Kaniuk’s 1948, a prize-winning Hebrew memoir of Israel’s war of independence.

Take this passage from Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood:

Memory is a funny thing. When I was in the scene, I hardly paid it any mind. I never stopped to think of it as something that would make a lasting impression, certainly never imagined that eighteen years later I would recall it in such detail. I didn’t give a damn about the scenery that day. I was thinking about myself. I was thinking about the beautiful girl walking next to me. I was thinking about the two of us together, and then about myself again. It was the age, that time of life when every sight, every feeling, every thought came back, like a boomerang, to me. And worse, I was in love. Love with complications. The scenery was the last thing on my mind.

Could you condense it? Make it fast paced and concise? You could… but the words have an almost rolling snowball-like effect. The feeling of emotional tension builds gradually, from a gentle tug to a full on sucker punch by the end of the paragraph. Language in literary fiction is a luxury, one to wrap yourself up in and enjoy.

7) The books are often open to personal interpretation

Harking back to 5), literary fiction does promote discussion. However, it isn’t only because our opinions of the story or the writing differ. Literary fiction is often felt differently, depending on our own experiences. Recently, I read The View on the Way Down, a book I loved. Yet some of the things that made me love this book, were the same things that others found it difficult to relate to. My personal experience made me more empathetic but also added to the sense that the author was not only telling the character’s story, but the story of thousands of others. For me, the book felt inclusive and comforting. For others, it felt exclusive, hinting at things they couldn’t fully connect with.

Even more astounding is the way that we can change our own views about a book as we age, experience different things, meet others and are influenced by their perspectives. As a result, not only can a book be read differently by each person in a group, it might also be also be read differently by an individual on each new reading. Like a repeat theatre performance, you will never see the story in quite the same way, from quite the same angle.

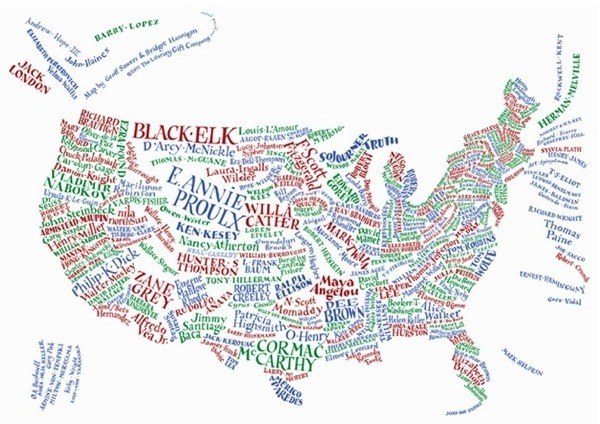

US author map, via Flavorwire

8) It might make you appreciate your genre fiction more

This isn’t a ‘literary fiction is better than genre fiction’ argument. Both have merit and great benefits. But have you ever noticed that when you’ve been thoroughly absorbed in a literary fiction title, finishing and moving straight on to something equally as lofty can seem overwhelming? At times like this, a dramatic thriller or a heartwarming romance is perfect. It can provide a wonderful read, one you potentially appreciate so much more because you just read something so completely different. Likewise, reading genre fiction and then moving on to literary fiction can enhance the different structure, pace and language. The either/or argument doesn’t work, when the two complement one another so well.

Even if that weren’t the case, the lines between genre fiction and literary fiction are becoming increasingly blurred and have been for some time, according to a New Yorker article, Easy Writers.

In 1995, Martin Amis dubbed Elmore Leonard “a literary genius who writes re-readable thrillers.” Skilled genre writers know that a certain level of artificiality must prevail. It’s plot we want and plenty of it. Basically, a guilty pleasure is a fix in the form of a story.

Appreciating both genres separately makes it easier to approach those books that manage to hit both targets. In a subsequent article – It’s Genre, Not That There’s Anything Wrong With It – the same author writes:

Grossman sees a qualitative difference between certain kinds of fiction while also insisting that good genre fiction is by any literary standard no worse than so-called straight fiction. Literature, Grossman believes, is undergoing a revolution: high-voltage plotting is replacing the more refined intellection associated with modernism. Modernism and postmodernism, in fact, are ausgespielt, and the next new thing in fiction isn’t issuing from an élitist perch but, rather, is geysering upward from the supermarket shelves.

The debate on this will be a long running one and the sources are many. Here’s what Slate’s Culture Gabfest had to say.

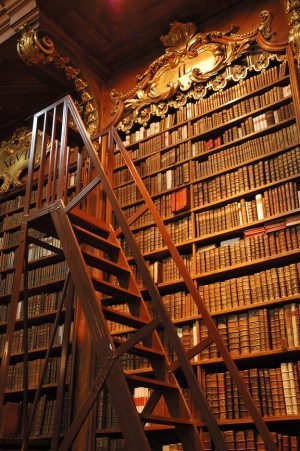

9) It’s often a chance to spend hours connecting with great thinkers – past and present

(Again, this isn’t confined to literary fiction, but it’s still a great plus point!)

How would it feel to spend a few hours absorbing the wisdom of Maya Angelou, the eloquence of Junot Diaz, the mathematical knowledge of Lewis Carroll, or Sir William Golding’s behavioural insights? Some of us may have the opportunity to be taught by some truly incredible professors and teachers, but luckily the rest of us are not totally deprived. We can experience the knowledge, experience and elegance of some of the cleverest minds in history, simply by opening a book and reading. To me, that’s remarkable.

Find out more at Neatorama, Voicu Minhea Samandan, Mental Floss.

10) Art echoes life

Sometimes it’s just refreshing to know that life – normal life, without zombies or mom-turned-assassins, or being swept off your feet by a billionaire – is interesting enough to read about. The old adage that the truth is stranger than fiction rings true. Literary fiction embraces that.

Tom Gauld, author of You’re All Just Jealous of My Jetpack

Sometimes the simplest stories can be the most beautiful. Whether the sweet poignancy of Norwegian Wood, or the historical beauty of Memoirs of a Geisha, literary fiction proves that stories don’t have to be full of swooning, car chases, bloody crime scenes or paranormal activity for them to be exciting. Moreover, these stories, with their strong links to real life, real events, real experiences, have an intense and lasting impact. That’s the reason my heart leaps into my mouth when I think of We Need to Talk About Kevin, or The Drowning People or A Prayer for Owen Meany. It’s why – 17 years after the first reading – Wuthering Heights still gives me chills, why 1984 still manages to feel prophetic rather than dated, why The Alchemist pushes through my cyncism to touch my heart.

We shape literary fiction. And – quid pro quo – literary fiction shapes us.

YES! As an aspiring author who toils in the realm of literary fiction, this article really hits home for me. Literary fiction is special in that it is fiction that offers the opportunity to both entertain you and change you – or at least change your perspective. But that’s a hit-or-miss proposition I suppose for literary agents who are looking for something that neatly fits into a category for publishers and is easily marketed to a reader-base. I wish I could write about zombies or vampires or zombies vs vampires or vampires romancing zombies or…but for me it boils down to the “allegiance to language” you reference. I love that phrase.