Following on from this week’s earlier post from Luz Aguirre of Mano a Mano, Mary Ellen Sanger joins me today!

Writing Time

by Mary Ellen Sanger

This past month has flown by. After a move from New York to Colorado, I was busy getting my license, rifling through the boxes in my storage unit, starting a blog, discovering where the best sushi is prepared, learning how to dress for a climate where the day and night temperatures differ by thirty degrees Fahrenheit and making new community to feel a part of things here. Part of my new community includes the women incarcerated in the Larimer County Detention Center. We write together every Wednesday evening. Wednesdays are a pin on my calendar to keep the pages from flipping by too quickly. Sitting with women whose clocks tick at a different pace is a reminder not to let a moment go by unobserved. And I remember…

When I was in prison in Mexico, I didn’t write with the women I was incarcerated with. I taught some informal English. I helped write a script for play. I wrote plenty of letters for people, love letters, confessions and pleas. But honestly, most of my time was spent with friends and my lawyer figuring out how to outsmart the baddies who had imprisoned me in the first place. And writing in my own notebook. Whole spiral-bound rafts of words that marked my moments. “There is a sparrow preening on the barbed wire.” “I didn’t get the blue broom today.” I said little but wrote for hours, to keep my head straight and to fill the long moments between waking and sweeping, a visit and sweeping, a call and sitting and sitting and sitting and sweeping and waiting and sleep. I recorded every moment in a frenzied attempt to stay attached to the straight lines on my pages as everything else spiraled and spun and ricocheted in a dizzy-making waves.

When I returned to the US after my release, I knew a few things. I was out of prison, but prison wasn’t out of me. And I had to keep writing. I joined the PEN Prison Writing Project as a mentor and a member of their fiction and poetry committees, helping to select winners in an annual contest which receives manuscripts from prisons throughout the US. I was trained to give writing workshops by the New York Writers Coalition, an activity that allowed me to be close to creativity through their sponsored workshops throughout the city. I wrote with people who were homeless, young women in a substance-abuse program, victims of domestic violence, people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s and young Latino immigrants and children of immigrants.

Writing is a great unifier. Nearly everyone can write. The method I use to write now with the women detained in Larimer County is the same one I used in New York: Here is a pen and some paper. Here is an idea. Write. Change the idea if you want. (Change the world if you want). Write on something else if you want. Write on not being able to write if you want. But write. And if you don’t want to write, write anyway. After seven years of writing like this, even with people who have great difficulty in expressing themselves verbally, I realize how hot our pens are. How fortunate I am to share these moments of fusion, as the pen liquefies some of our barriers to knowing ourselves and expressing ourselves. It just happens. The women write of being beautiful. The write of longing and lust. They write stories that make each other laugh and yes, some of them cry as they bravely read the words they discovered in themselves on the page no longer blank.

My Wednesdays are a pin on my calendar. I remember prison, and the women I knew inside who expressed themselves in yarn and thread to make purses that would someday hold pesos and napkins that would someday hold tortillas. I wish now, that I had been able to share a hot pen with them to create words that held there, in the moment, the enormity of one tear or one slow shuffle across our courtyard, from dawn to dark. Writing holds no key to the door out, but finding the door in is nothing short of miraculous.

Excerpt

Two guards armed with clubs led me through a concrete corridor following a delicate ribbon of sun, hashed by the shadow of crossed wire overhead. Along the edges men chattered, seated on concrete blocks or on the ground in informal groups. They hand-twisted copper wire into bicycle shapes. Some painted sailing ships on old light bulbs. Others drew long, curved needles through tough leather hides to make soccer balls.

“Put that one aside for me, man!”

“Look at that! A sweet new face, compadres!”

They pursed their lips and whistled, blew kisses. I didn’t feel threatened—I had two hulking male guards with me—but I knew the numbers: 110 women, 1500 men and one and only one gringa. I would stare, too, if I were fighting the boredom of their gray walls. Concrete floors, black uniforms, and suddenly one pale-skinned sun-streaked blonde.

The guards escorted me to the women’s compound, their heavy boots careful to match the pace of my sandals. They didn’t rush me.

“We’re almost there.”

“The women inmates have sewing classes. Art. Typing. You’ll have lots to do.”

Welcome to Ixcotel Penitentiary.

Their black heels in steady cadence, a club swaying at the hip – now they were the authority I would have to obey. I hadn’t had much experience with authority other than my own inner voice, which often whispered. If I ignored my own whispers, I might end up discontent or caught in the rain with no umbrella. Now there was a club to factor into the equation. To the guards, we walked toward the beginning. To me, the end. My sandals dragged along the last few meters before the gated entrance to the women’s compound, prolonging what was left of not being in there, with them.

The boss lady met me at the entrance. Once the guards passed me off, they pushed the heavy door closed behind us. It vibrated for far too long after the snap of the lock—a hum of metal on metal that intensified as I entered the buzz of the compound, where no one was sitting still, no one was quiet. The boss lady, fiftyish, wore a short belted dress checkered in blues and red. Her duo-tone ponytail, dark roots with bottle-blonde, was gathered tight at the top of her head like a fountain. She had penciled a warning in the severe black arch of her brows. “Don’t mess with me.”

“Check in with the receiving guard and I’ll be back when she’s done with you.”

Done with me.

It wasn’t like drowning; I could still hear. Screams bounced off two-story concrete block walls. It wasn’t like suffocation; I could still smell. Cigarette smoke clung to a wave of rancid oil from the kitchen. It wasn’t like being hit by a train or falling into a crevasse, my feet stepped square on the ground. Not a heart attack. Not a black hole. It was jail-prison-penitentiary-la cárcel. It was injustice-unknown-freedom erased. It was all of these things. It was all I had at that instant and it was nothing. A sudden loss, a darkening, a plummet.

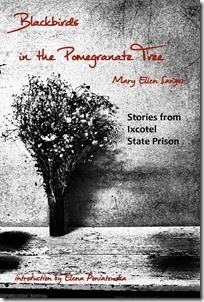

About Mary Ellen Sanger

Mary Ellen Sanger lived for 17 years in Mexico, and has published short stories and poems in Spanish and English in several Mexican journals and in online venues. She was a 2007 finalist for the Gift of Freedom from The Room of Her Own Foundation. Her essay “A Grammar of Place” was anthologized in Mexico, a Love Story. “Blackbirds in the Pomegranate Tree: Stories from Ixcotel State Prison” focuses on her experiences with other incarcerated women while she was falsely imprisoned for 33 nights in Mexico in 2003. For six years she led workshops for New York Writers Coalition (a Spanish-language workshop for Hispanic immigrants and their families at Mano a Mano and one for people in the early stages of memory loss at Riverstone Senior Life Services in Washington Heights). She has been involved in several prison-related projects, as a member of the fiction committee for the PEN Prison Writing Project, and as a long-time supporter and volunteer for the award-winning documentary “Presumed Guilty (Presunto Culpable).” She is currently part of a team facilitating writing workshops for women detained in the Larimer County Detention Center in Fort Collins, Colorado.

Find out more about Mary at her blog.

About Blackbirds

Mary Ellen Sanger had made her life in Mexico for 17 years when she suddenly found herself in prison in Oaxaca, Mexico, arrested on invented charges. She spent 33 days in Ixcotel State Prison in the fall of 2003.

Mary Ellen Sanger had made her life in Mexico for 17 years when she suddenly found herself in prison in Oaxaca, Mexico, arrested on invented charges. She spent 33 days in Ixcotel State Prison in the fall of 2003.

These stories of the women she met there, illuminate her biggest surprise and her only consolation in prison: the solidarity that formed among the women she lived, ate, swept and passed long days with while inside.

Nine lyrical tales show the depth of emotions that insist on their own space, even in these harshest of circumstances.

The largest and brawniest woman in the prison, doing time for armed robbery, kills a rat with her foot, then turns to the author for help with a very special letter.

Another young woman, only nineteen years old, has already been in for three years, guilty of kidnapping her own child.

And Ana, a political prisoner, teaches the author about creative ways to turn the tide, one including frog-eating snakes.

Mary Ellen weaves her own tale through the stories. Accused of a crime that doesn’t exist by a powerful man in Mexico, she depends on the fierce solidarity of friends on the outside, and a brilliant lawyer who trusts in the rule of law… even in Mexico.

The women incarcerated in Ixcotel State Prison said that the blackbirds chattered in the lone pomegranate tree in the courtyard whenever a woman was about to be released.

Blackbirds in the Pomegranate Tree: Stories from Ixcotel State Prison, published November 2013.

Get a copy now or join the discussion on the Facebook page

[…] I’ll close with a literary note. Almost two decades ago, American writer Mary Ellen Sanger spent six weeks in a Mexican prison. I met her years later at the home of New York-based author Talia Carner as part of a […]